THE EVOLUTION OF THE N.Z. SOCIAL FORMATION

We proceed from the level of the material base, using the model of interlocking circuits outlined above, to show how that approach can explain the evolution of the N.Z. social formation. The most important interlock came historically from N.Z.'s (or specifically the PFM's) role as a supplier of cheap foodstuffs to the U.K. in return for the investment of U.K. money capital as well as providing a limited market for British manufactures (see (7) above). This connection between N.Z. capitalism, based mainly on the PFM, and U.K. industrial capitalism, was to completely determine the historical development of the N.Z. social formation. At the same time it operated as a counter-tendency to the falling rate of profit in the U.K. by cheapening wage-goods and returning interest on the national debt.

Since this interlock is so important in setting the limits to historical development in N.Z. we must give an explanation of its origins. This involves tracing the causal interplay between the economic base, represented by the interlocking turnover circuits, and the agents who perform class functions within these circuits, and the superstructure of politics (the imperial connection) and ideology (nationalism). Our explanation of the timing of N.Z. settlement and of the subsequent development of the CMP must therefore begin with the question of the causes of colonisation, and in particular with an examination of the ‘land barrier’ in mid-nineteenth century Britain.

3.1 The Land Barrier

Our analysis of the historical circumstances which caused white-settler colonisation is based on the barrier of landed property to further capital accumulation. Marx establishes the connection between agriculture and industry as follows:

In the period of the stormy growth of capitalist production, productivity in industry develops rapidly as compared with agriculture, although its development presupposes that a significant change as between constant and variable capital has already taken place in agriculture, that is, a large number of people have been driven off the land. Later, productivity advances in both, although at an uneven pace. But when industry reaches a certain level the disproportion must diminish, in other words, productivity in agriculture must increase relatively more rapidly than in industry (TSV, II, 110).

From about 1800, increased productivity in agriculture was retarded by the remaining feudal barrier to accumulation on the land - landed property in Britain and the protected colonies. A landlord class extracted an absolute rent from tenant fanners and consumed rather than invested this surplus-value as capital (Marx, Capital Vol. Ill, 748-813). This barrier to agricultural investment prevented a cheapening of the elements of constant capital (raw materials) and wage goods (food etc) in industry acting as a brake on the expansion of industrial capital.

The consequence was a prolonged period of relative economic stagnation, of small booms punctuated by commercial crises, and accompanied by agricultural labourer’s riots, Chartist demonstrations, overpopulation, pauperism and crime (Hobsbawm, Industry, 56-108).

Thus the encumbrance of landed property to the further development of industrial productivity (relative surplus-value) was expressed politically and ideologically as a class struggle between the landlords and the industrial bourgeoisie. Parliament was still the preserve of landed property, propped-up by the mercantilist system, the extraction of absolute rent in Britain and the colonies (Marx, Capital Vol. Ill, 791; Mandel, MET, 282-292). The breaking of the land-barrier came only after a lengthy struggle in which the industrial bourgeoisie asserted its parliamentary supremacy, abolished the feudal rump of mercantilism and put ‘free trade’ in its place. There followed between 1850 and 1870 an unprecedented boom based on new sources of cheap food and raw materials which established Britain as the 'workshop of the world'.

Equally important for our purposes was the land barrier as the prime cause of white-settler emigration. While the process of the expropriation of agricultural labourers was continuing apace, together with the depopulation of Ireland, a stagnant industry could not provide employment for this surplus population. In order to escape wage-labour and pauperism large numbers emigrated to the colonies. Between 1815 and 1859 a total of 4,917,598 persons emigrated from the U.K. to all parts of the world. Over the same period approx. 684, 000 emigrated to Australia and New Zealand (Merivale, Colonisation, 166). The outflow of white-settlers to the ‘new lands’ added an important dimension to the development of the CMP in Britain. It established not only new sources of surplus-value, but new ‘little Englands’ i.e. social formations where ‘fragments’ of the British social formation comprising economic, political and ideological levels, were grafted onto pre-capitalist formations, producing a hybrid type of colony.

3.2 The Penetration of the Capitalist Mode

It follows that the penetration of the CMP into the Maori social formation occurred at all three levels -economic, political and ideological. The task is to determine the relative impact of each level upon the colonisation process. It is clear at the outset, that the bourgeois approach to colonisation, in examining in minute detail the motives of those concerned (missionaries, the Colonial Office, settlers), begs the question of economic determination in the last instance (Sinclair, A History, 65; Ward, Justice, 24-40). This is the method of the ‘isolated instance’ as opposed to that of ‘structural causality’. In terms of our explanation, these actors were all agents of the CMP, but they operated at different levels. The settlers most directly represented the class struggle arising from the land barrier in Britain. Consisting of those who were escaping high rents in the hope of getting the benefit of ‘founders’ rent’, or of the unemployed hoping merely to produce their means of subsistence in the land, they were either aspiring capitalist farmers or independent producers (Marx, Grundrisse, 279; TSV, 11, 239).

Of the settlers, it was the systematic colonisers who were the most influential in causing the imperial state to annex N.Z. They persuaded the British state agents that colonisation would provide a solution to the social and political problems of the time by serving as an outlet for surplus labour and capital. Merivale, for example, went to great lengths (in his capacity as Oxford don) to demonstrate that controlled emigration would not deplete the reserve army of labour below the numbers necessary to hold down wages at home (ibid, 164-165). The clinching argument was that the expenses incurred would be paid for by a tax on the wages of the emigrating workers in the new colonies (ibid, 158).

The imperial state's annexation of N.Z. can therefore be seen as a necessary expense incurred in the maintenance of law and order as a condition of the reproduction of the CMP in Britain (see 2.4). Whether these expenses were involved in putting down rebellion at home, transporting convicts, or pacifying unruly 'natives' - Afghan, Chinese, or Maori - the purpose was the same. The apparent contradiction, in bourgeois terms, between the expense of annexation and the absence of any direct economic benefit (raw materials, labour, market) in a period of free trade, which can only be ‘explained away’ by introducing the myth of ‘moral suasion’ (Wards, Shadow), is in the final analysis, no contradiction. Native protection was simply a slogan providing-ideological cover to the geographic extension of the imperial state's political-legal function in reproducing the CMP (see 2.6).

Once we have established that the class interests of the settlers were not in contradiction with the imperialist state, the highly over-rated role of the missionaries and humanitarians becomes clear.

They are revealed as bourgeois agents in the reproduction of ideas at the ideological level. Though these ideas (anti-slavery, native protection, civilising mission etc) are determined in the last instance by the interests of the industrial bourgeoisie, the ideological agents do have great ‘relative autonomy’ in practice. Since the function of bourgeois ideology is to represent the values of capital as ‘natural’ and ‘universal’, we must expect well-intentioned missionaries to perform this task literally in the geographical sense, often penetrating pre-capitalist social formations in advance of the market. According to Merivale, religion is the basic means by which ‘civilisation’ is introduced to ‘savage tribes’; “For in what mode are we to excite the mind of the savage to desire civilisation?” (ibid, 524).

The immediate impact of the ideological ‘civilising mission’ in N.Z. was to challenge the dominance of the Maori chiefs (elders) in the reproduction of the MLM. In this they failed for the introduction of commodity trade allowed a rapid adaptation of the MLM to commodity production (flax, wheat etc) but still under the dominance of the elders (cf. Firth, Economics, 482). Thus the combined efforts of the ‘advance guard’ of the CMP, the missionaries and traders, were insufficient to subordinate the MLM, convert its means of production and labour-power into commodities, or to set-up the settlers’ PFM. The explanation is to be found in the key role of the elders in the MLM (see Section 2.7). Since the elders were not a ruling class;

they could not be used in alienating the land without destroying their ideological dominance in the MLM. By 1860 the growing pressure from the settlers for land put this role to the test. A number of chiefs responded by reasserting their ideological command over the MLM in the from of the King Movement to prevent the loss of their remaining land. This resistance was interpreted by the imperialist state as a political rebellion (implying a Maori King and a Maori state) justifying the use of state force to break the elders’ control of the MLM, and in to seize the land in compensation. With the elders' control broken, the imperial state, as midwife of history, introduced the CMP into N.Z., establishing the PFM and articulating the remnants of the MLM, both under the dominance of capital.

Following the intervention of the imperial state to establish by force the conditions for the CMP, the way was clear for the settlers to assume responsibility for self-government. The striking difference between the ‘new lands’ and the ‘old world’ was the absence of landed property. Marx, in his discussion of the ‘new system of colonisation’ (Capital Vol. I, Chap. 33) shows how free land is a hindrance to capital accumulation of a different sort to landed property, since it prevents the formation of a wage-labour class without its means of subsistence. That this was the case in N.Z. together with the refusal of the British Crown to allow many of the N.Z. Company's dubious claims, accounts for the failure of the Wakefield system to dominate agriculture. Had the Company been able to establish ownership of the vast tracts of land it claimed, then it would have been able to reproduce in the colony a system of landed property, whereby a few landlords could have extracted absolute rent from agricultural labourers and tenant farmers. While it is true that in the period up to 1890, a landed squattocracy controlling large landholdings did exist, this was in the nature of extensive capitalist farming of wool and wheat, and did not constitute a barrier to capital investment in increasing agricultural productivity. What was established in New Zealand in this period was therefore neither landed property, nor large-scale capitalist farming, but rather the grafting of the old stock of the PFM onto the new roots of ‘free land’ through the agency of the settlers’ state.

It is important to stress the key role of the state as it figures prominently in bourgeois explanations of N.Z.’s ‘national development’. The settlers used the local state “to hasten, as in a hothouse, the process of transformation.. . to the CMP” (Marx, Capital Vol. I, 915). With the destruction of the MLM, the state legislated ‘peaceful’ means of appropriating any remaining Maori land of value (Ward, Justice. 185). It encouraged the immigration of the land-hungry and assisted smallholder settlement with crown leaseholds, loans and other forms of subsidies. Most importantly, it borrowed large amounts of British finance capital to lay down a productive infrastructure, social overhead facilities and the necessary links to international trading networks. It was a very good example of the use of the national debt described by Marx as one of the “most powerful levers of primitive accumulation” (Capital Vol. I, 706-707). While the benefits of the developments made possible by such borrowing went mainly to direct producers, “financiers and middlemen”, much of the burden of interest on the national debt fell on the working-class.

Bourgeois conceptions of the role of the state in the articulation process are of two sorts. The neo-classical view reduces the state and ideology to epiphenomena of the international market (Blyth, Industrialisation). N.Z.’s comparative advantage is in its agricultural specialisation - fertile land, plus capital equals ‘take-off’. Following the classical political economy, this view does not recognise exploitative class relations or the capitalist nature of the state. Its perspective is thus entirely limited to the appearances of the market. The more common view of the role of the state is that which draws on the radical tradition of the ‘progressives’ (Reeves, Experiments, 59-102; Sutch, Poverty, Colony, etc). It gives causal primacy to radical ideas which are then translated into progressive legislation to control the ‘excesses’ of the market, and to regulate capital and labour in the ‘common interest’. It acknowledges but does not understand the key role of the state. Following Reeves and Stout, the state is seen as ‘neutral’ and above classes, not merely ‘relatively autonomous’ , but capable of abolishing classes and capitalism itself (Bedggood, State Capitalism).

It is clear that the bourgeois historiography in the ‘long Pink Cloud’ tradition (Sinclair, N.Z.), in making radical ideas the prime cause in N.Z.’s history, has not looked beneath the level of the superstructure to discover the final cause of bourgeois radicalism. A classic example is the role of radical ideas and policies in land settlement (Marx, TSV, II, 44). Once the objective of the ‘nationalisers’ or ‘single-taxers’ had been realised, namely land-ownership, radicalism was transformed into a conservatism of private property. Therefore, to take the isolated instance of radical ideas as the independent and ultimate cause of national development, is to replace an economic determinism with a cultural determinism in the ‘last instance’ i.e. idealism. While the semi-colonial state was an important instrument in the development of capitalism in the N.Z. social formation, it was not sufficient. It was the new land combined with immigrant labour, producing a high rent plus a secure return on the national debt, which in the last instance, determined the politics and ideology of ‘national development’.

3.3 The Reproduction of Capitalist Social Relations

In summary then, the articulation of modes which evolved in the N.Z. social formation, reflected in the last instance, the ability of the peasant smallholder to achieve state subsidised settlement and to benefit from ‘founders’ rent’ on relatively fertile land (Murray, Value, II). This s provided the material circumstances for the establishment of the CMP in N.Z. and the capitalist domination of a new source or surplus-value that entered into the imperial circuit, furthering accumulation both in Britain and the semi-colony. But the whole basis of the extension of capitalist accumulation in N.Z. rested upon the reproduction of capitalist social relations. The crucial role in this process was played by the comprador bourgeoisie, who as linking agents, managed the transmission of capitalist social relations into the ‘backwoods’ of the PFM in the new colony. Though now possessing land, the settler lacked capital, a crucial fetter to his expansion beyond producing his means of subsistence; and the comprador provided it if the state did not also. The merchant provided commodities for use, and credit for their sale and purchase. The finance capitalist provided capital for the land, and the banker backed them both and directed customers to them. The role played by the comprador class has been nowhere adequately stressed in the bourgeois literature, and not even by so-called radicals, who in their concern with ‘foreign control’ ignore the bourgeois class that has acted as the local agents of most forms of ‘foreign control’ (e.g. Sutch, Takeover).

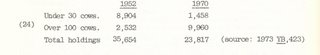

The class relation which became the basis of the pattern of interlocking circuit dependence that had emerged by the 1930's was one in which the peasant smallholder had become a form of wage-slave, contributing surplus-value to the comprador class. This form of exploitation follows from the key role of the comprador in extracting surplus-value, in controlling the marketing of the primary products, and requiring the farmer to meet his fixed charges out of normal profits and even wages (see next section). This extraction was expressed in a disguised form in accounts as interest on mortgage, rent paid, commission to stock and station agents, freight charges, insurance on chattels,(re-possession on default of mortgage repayments)etc. in total accounting to about 45% of all farm income in normal times, and 100% during the Great Depression (Weston, Farm). The comprador had in effect, replaced the landlord as an agent in extracting surplus-value. Though Condliffe, one of the more perceptive of bourgeois economic historians, recognised that the N.Z. ‘freeholder’ had by the early 20th century, “exchanged the landlord for the mortgagee”, he refused to admit to any more than the possibility of his ‘exploitation’ by the comprador class (NZ, 277).

On the basis of this analysis we conclude that the grip of the finance bourgeoisie, both British rentier and local comprador, on the labour process of the peasant producer, did not cease to tighten and consolidate the now traditional pattern of semi-colonial specialisation in the international division-of-labour. Though they replaced the landlord class in extracting surplus-value from agriculture, their role was not to hold back the investment of capital in agriculture. They accumulated rather than consumed the surplus-value off the land, facilitating the circuit of capital into agricultural production in the form of productive capital, providing money capital for investment in the nascent branches of industrial capital in N.Z., and of course re-circulating money capital into British and other international circuits.

While Marx and others have written on the articulation of CMP and Peasant Modes, there is no fully developed theory of what we have call called the PFM in the white-settler states. It seems to us that the potential of this form of articulation has been underestimated in circumstances where it is introduced into a semi-colonial setting characterised by (a) an absence of feudal landed property, (b) the dominance of a capitalist comprador class, and (c) in association with a highly interventionist, modernising local state. It is clear that when these conditions prevailed, as in N.Z., the PFM has, in the form which we have described above (2.7), undergone remarkable transformation.

3.4 Unequal Exchange

Our analysis of the production and extraction of surplus value in the N.Z. social formation so far leads us to the position of accepting that same form of ‘unequal exchange’ of value operates to maintain

N.Z.’s subordination to international capital. This subordination shows up in many forms but is most obviously related to the international flow of export commodities and the value relationships underlying these flows. Consequently we reject any analysis of ‘unequal exchange’ in the tradition of Emmanuel’s work, which begins from the level of wages, prices or terms of trade, and tries to deduce explanations of ‘exploitation' and under-development. Very briefly, Emmanuel argues that inequality of wages as such, all other things being equal, is alone the cause of inequality of exchange (Unequal, 613). But of course all other things can never be equal and it has become clear that arguments which begin at this level cannot further our understanding of the problem. For example, in Clark’s discussion of Australia, he records that Australian wages have been generally higher than British wages. He can only avoid the absurd conclusion that Australian workers have exploited British workers by calling for more pseudo-statistics! (Clark, Unequal).

Yet for all the polemic against Emmanuel, little empirical or theoretical work has been done to counter the appeal of his thesis. Bettleheim and Palloix have pointed to the logic of reproduction as the starting point, and Barratt-Brown has marshalled some data to demonstrate that the level of wages is a mirror image, not a determining factor of unequal exchange (Economics, 235). By contrast, we have argued that the position of various classes in relation to the overall reproduction of capital is what is fundamental, and that this must not merely be asserted but actually demonstrated. This we propose to do, beginning first with an attempt to explain the phenomenon of ‘unequal exchange’ as a particular case of absolute rent in the N.Z. historical context. We start therefore by explaining the basic idea of absolute rent and then adapting it to the problem of unequal exchange. Then we show how responses to this original form of unequal exchange help explain the current pattern of relationships prevailing in N.Z.’s international trade in agricultural commodities.

a. Marx's Theory of Absolute Rent

Marx defines absolute rent as that component of surplus-value which does not enter into the process of equalisation of the rate of profit across departments (Capital Vol.III,760-761). It reflects the monopoly of ownership of a particular resource employed in the production of commodities under the CMP. In Marx's example, the resource referred to was land and it was the landlord class which acted as an obstacle to the free flow of capital and the equalisation of the rate of profit in agriculture with that in other departments. In demonstrating the case of absolute rent, Marx defines three levels of analysis

(1) the Value of commodity i, understood here as an agricultural commodity, and comprising the elements W1= Ci + Vi + Si

(2) Prices of Production (Yi) comprising costs (Ci + Vi if we ignore the transformation problem) plus average profits and

(3) a monopoly-price or modified price (Xi) which equals costs plus profits, at an average rate if the farmer is a '’true’ capitalist, plus absolute rent or excess profits.

These 3 levels are defined in the diagram below.

(NB: In what follows we ignore the so-called transformation problem which is a red herring for the purposes of the present discussion anyway).

In this example, Xi >Yi, i.e. the modified price exceeds the price of production by the full amount of the absolute rent, since we assume all items of costs and profits to stay the same in both cases. Absolute rent is added as a monopoly profit to give a modified price which is consequently higher than the price of production (Yi). Now whether absolute rent is added on to the price of production (Yi) or is deducted wholly or in part from Yi depends on market conditions (supply and demand) (Capital Vol.III p762) . It also depends on the relations of production in agriculture. Normally under capitalist production relations in agriculture absolute rent is by definition marked up on top of average profit from farming since no capitalist farmer would invest his capital at below average profit and no landlord will let him use the land without paying rent.

Now at first glance, there would seem to be little relevance in all this to the N.Z. case. Not only was there no landlord class, but no effective obstacles to settlement on the land existed. How then do we establish a case for unequal exchange along these lines?

b. Adapting the Basic Theory

We recall the point made by Marx and Lenin that colonial super profits were the most important counter-tendency to the falling rate of profit. Such super-profits in turn imply the existence of monopoly control of finance capital at the centre which could act to eliminate competition and prevent the general process of equalisation of the rate of profit everywhere. But this still does not indicate what the source of unequal exchange was in the periphery. To explain this we refer back to our discussion of the causes of settlement in N.Z. (3.3). Our general thesis was that whilst monopoly over landed property (‘modern landed property’) was never established in N.Z., this was replaced by another form of monopoly, that of finance capital, owned by the comprador class. While the process of settlement was such that some acquired large holdings, the majority were peasant smallholders, buying and selling on the local market. After establishment of the main trading links with the U.K., these smallholders became increasingly indebted to merchant bankers for the credit needed to purchase and develop their holdings, consolidating the relationship with the comprador class which extracted the surplus-value from the direct producer in the form of an absolute or monopoly rent, this time understood as a monopoly of large money capital.

Now the question arises as to where this rent came from. Was it paid out of a modified price Xi in excess of Yi by the full amount of the rent, as in the original analysis outlined in Section (a) above? Or was it absorbed into Yi and taken out of some combination of wages (i.e. the value of labour-power of the snallholder, Vi) and a rate of profit that was average or less than average? The latter could only occur if the occupying smallholder was not a true capitalist, i.e. did not demand an average rate of profit on his capital.

Moreover, its impact on different smallholders’ individual rates of profit would depend on the differential rent from their new land in the colony, i.e. the disparity between their individual costs of production and the average price as determined for them by the market. We are referring here to DR1 which Marx defines as the varying yields from land of equal area with equal applications of constant capital, arising out of differences in fertility and location with respect to the market (Capital Vol. III 647-673). The effect of greater yields would be to reduce the unit cost of production for the favoured smallholder, and raise his rate of profit above the average. However, we cannot assume that in N.Z. all the land settled was better than older lands under cultivation in the countries of older civilisation (Capital Vol. III p.769). So, in what follows we assume at first land of average fertility and then in Section (c) consider the impact of differential rent on our initial conclusions about the distribution of surplus value produced.

In trying to determine the distribution of surplus value we have to consider only 2 alternatives - do we assume the average smallholder realised an average rate of profit or a less than average one, in the conditions of settlement of N.Z.? We suggest that probably the latter was what occurred at least in the early period. The two main reasons for this were (1) that under pioneer conditions, settlers were more concerned with producing their means of subsistence and reproducing their capital at a minimum rather than an average rate. That is, they valued actual possession of the land highly. (2) Market conditions also operated in the same direction. The comprador class had an interest in increasing its share of the surplus value produced at the expense of the direct producer, so keeping the modified price Xi low and the price of the new colony's commodities down. This was after all the basic function of the new colony - to cheapen costs at the centre. The comprador would therefore attempt to take his excess out of average profit of enterprise, rather than mark-up the price of production and lower the colony's international competitiveness. In all cases, however, the share of the comprador in the form of a monopoly rent constitutes unequal exchange.

As a simplified abstraction of the likely pattern of unequal exchange we offer the following example. We stress that we are dealing at this stage only with land of average fertility.

Here Ci is constant capital in branch i; Vi is variable capital, Si is surplus value, R is the average rate of profit calculated in the usual way - i.e. assuming the identity between aggregate surplus-value and total money profits. R' is the rate of merchant profit on merchant comprador capital advanced (Mi), and R’ is the analogous rate on enterprise capital advanced (Ki). We divide the N.Z. social formation into the agricultural sector (or circuit) (A) the industrial sector (or circuit) (M). The table below shows the general relations of exchange which finally prevail after the modifying influence of the comprador class is taken into account.

In the table, R = 20% before modification by merchant finance capital, i.e. before deduction of monopoly rent. After modification, the merchant rate of profit in (A) exceeds that in (M) and merchant capital in the latter receives a rate of return approximating the overall modified rate or enterprise profit in (M). The rates of profit finally received are:

(The figures in brackets are actual modified profits received in money terms) .

Under this solution ∑Wi = ∑Yi = ∑Xi, but individually values and prices (either Yi or Xi) diverge. The family smallholder ends up with a less than average rate of enterprise profit and turns a monopoly rent over to the merchant comprador in the same way as the English tenants turned over rent to their landlord as the condition of their being permitted to invest capital in his land (Capital Vol. III, 626).

In our example, the comprador class, therefore, inserts itself in an intermediary position between the dominant capitalist mode and the dependent PFM forcing prices received by the PFM down low enough so that, even after modification by monopoly margins, the market price was still low enough to be competitive.

Unequal exchange, as it operates here, is a form of monopoly rent extracted by a comprador class from the surplus value produced in agriculture as a consequence of that class's control over the movement of capital into that branch of production. But it clearly cannot rest there. This monopoly will be subjected immediately to countering forces. For instance, how long will it be before manufacturing capitalists attempt to become merchant compradors? We must now turn to a discussion of the counteracting forces.

c. Countering Obstacles to Extended Reproduction

It follows from our example as it stands, that the direct producers of the PFM would have had difficulty reproducing their conditions of existence, or even making improvements to compensate for declining natural fertility of the land. As such our illustration underestimates the potential for expanded reproduction within the PFM, a potential which history shows to have been clearly realised. In the first place, we have ignored Differential Rent 1, i.e. differences in fertility and location which would imply that, although on average, the rate of enterprise profit in (A) was kept low, there were wide variations around this average. Farms with above average DR1 could therefore earn rates of profit equal, or even in excess of the average for the formation as a whole (20% in the example). For these producers, then, there would be fewer obstacles to accumulating capital and extended reproduction. Such disparities in DR1 therefore, (e.g. above average fertility or exceptional location) underlie our explanation of the differentiation of the peasantry, as outlined in Section (2.7) above, into 3 classes or fractions after about 1890. The bourgeois fraction was favoured in its ability to invest their own capital in the general modernisation of their holdings, and so reduced their dependence on the comprador class.

However natural fertility of the soil has to be replaced, and the pace of mechanisation, or raising of the organic composition had to be maintained and in this process the State played a crucial role. The State's activities may be summarised as intervention in the PFM to sustain extended reproduction by limiting the monopoly control of the comprador class over the movement of capital. This was achieved by methods which influenced both DR1 and DR2 although a clear distinction between the two is difficult to maintain. The most important measures were State subsidies in the development of improved methods of cultivation, higher yielding stock, improved methods of fertilisation, improved public works etc. Secondly, the State limited the monopoly of the comprador over the supply of credit by offering cheap State loans for both settlement and development. Finally, particularly after the onset of the depression of the 1930's, the State itself became a monopoly in the acquisition of smallholder dairy production in an attempt to bolster squeezed profitability and to undertake more ‘rational’ marketing of dairy products. (Such, Security, 183-6)

As a consequence of these measures and others too numerous to mention, the State ‘nationalises’ the major costs of agricultural production and re-circulates excess profits at least partially back to the direct producer, holding down the share of the comprador class of the surplus value produced. The direct producer's rate of realised profit would converge upwards to the overall average and thereby allow for extended reproduction to go ahead more rapidly.

But while State intervention breaks the monopoly control of the comprador class over the PFM in subsidising the costs of agricultural production, this only modifies the basic pattern of unequal exchange, it does not reverse it. The fact that such commodities still sell at modified market prices below their values represents unequal exchange out of the PFM in the conventional sense, i.e. a divergence of value from price. The State operates to redirect some of this transfer of surplus value back into the PFM by means of subsidies paid out of general tax revenues.

In addition to this conventional form of unequal exchange, we have added another relating to the monopoly ownership of capital by the comprador class. We have pointed out the limits placed on this monopoly by the State. In terms of the interlocking circuit model, the semi-colonial State, therefore, encourages the reproduction of international capital by transferring value in the form of State subsidies into agriculture, hence countering the tendency for agricultural production to stagnate.

To conclude our analysis of unequal exchange in agriculture it follows that the transfer of value out of agriculture, made possible by the combination of 1) a modern progressive form of land tenure in the semi-colony, 2) high differential rent and, 3) State intervention, provided a source of capital which could be used to ‘develop’ domestic manufacturing.

3.5 Contemporary Patterns of Circuit Interdependence

The previous sections have been concerned with the application of the interlocking circuit model to the analysis of the development of capitalist dominated agriculture in the N.Z. social formation. To some extent we have presupposed the existence of the Industrial Capital Circuit in our discussion of the flow of surplus-value via the state into the agricultural branch. In this section then, we extend the analysis to include the development of the industrial circuit into N.Z. and to demonstrate its impact on contemporary ‘economic’ relationships affecting the social formation, and on the pattern of social relations, or ‘class structure’. Though we cannot give more than an outline of the growth of the circuit in this paper, we emphasise its importance in the full development of the CMP in N.Z. It represents the further development of the CMP in N.Z. from the initial limited interlock of British capital with the PFM, through the establishment of branches of domestic manufacturing, to the present complete penetration of industrial capital into all branches of production accounting for 3 to 4 times as much as agriculture in the statistics on national production (Year Book, 1977).

What is quite distinctive about this development is that while it followed a sequence of ‘stages’ from the introduction of the PFM, to simple manufacturing, to later advanced production by international capital, it did so at a much more rapid rate than the original capitalist transition because it occurred in the context of the already established CMP and as the result of a highly interventionist local state. This meant that the pre-conditions for capitalist manufacture, namely 1)- capitalist dominated agriculture, 2)- wage-labour, 3)- industrial capital and 4)- a market, were rapidly realised by means of their displacement from the British social formation and their re-location in the semi-colony by the agency of the local state. We have emphasised in our previous discussion the influence of the state in establishing capitalist social relations in agriculture by means of the National Debt, using U.K. finance capital to develop the infrastructure of ports, communications , etc. for the full development of capitalist farming. This provided the first condition for manufacture, i.e. wage-goods for a working-class.

The state created the second condition, the working-class itself, by means of the assisted immigration of would-be settlers who finding themselves landless had no choice but to work for wages. The creation of wage-labour in the colony was not therefore the result of the original Wakefield scheme, but that of state schemes that applied the same principles of using the revenue from land sales to pay for a supply of immigrant wage-labour.

The third condition, industrial capital, arose out of the process we have discussed above. We saw that the accumulation of capital from the PFM, whether by the comprador class or the peasant bourgeoisie, was sufficient to increase agricultural production. It also provided the necessary money capital for investment as productive capital in the industrial circuit as soon as the combination of conditions required for domestic manufacturing occurred. This conjunction came about during the Long Depression when the pool of unemployed drove down the value of labour-power to the point where the local cost of production (at low organic composition and high absolute rates of exploitation of men, women and children) together with tariff protection (in 1888) made domestic import substitution of some commodities profitable for the local capitalist class (Sutch, Poverty, 106).

Apart from the development of primary processing industries, either cooperatively owned, or owned by capitalists (see (11) above), and their more recent extension into areas such as paper pulp etc., the three main branches of domestic manufacturing established after 1880 were:

(1) - Production of Wage-Goods: articles of consumption for the working-class, beginning with clothing, shoes etc., and incorporating a widening range of commodities entering into the value of labour-power E.g. TV’s, domestic appliances, motor cars (see (9) above).

(2) - Production of Capital Goods for Agriculture: the local production of previously imported machinery, farm implements, topdressing aircraft etc.

(3) - Production of Capital Goods for the Wage-Goods branch: a more recent tendency since as we pointed out in 2.5, the production of capital goods is usually the speciality of the Industrial Circuit in the core capitalist states, e.g. steel for construction, plastics for consumer durables etc.

Though these domestic branches of production were established and sustained by means of state protection (tariffs and import controls etc) they nonetheless represented a new source of surplus-value production open to international capital. As a result, from the 1880’s to the present day, we find that all branches have been penetrated by ‘foreign’ capital which has moved to take advantage of the development of the CMP in the N.Z. social formation, drawing the formation further into the international circuits of capital and reinforcing the semi-colony's extraverted dependence.

We can describe the contemporary N.Z. social formation therefore as an immensely complicated system of interlocking circuits of capital spreading throughout its articulated economic base, and now augmented by an increasingly important branch of manufacturing production. The basic logic of the whole unity is one of circuitous interdependence, each circuit feeding or linking at some crucial stage with a foreign counterpart. The most crucial interlocks, in the context of our current discussion, are as follows:

(a) The Level of Production

(i) imported materials of labour feed into agricultural production for re-export or for industrial manufactures (oil, chemicals, raw fertilisers etc). We may call this an ‘import-output’ linkage.

(ii) Imported machinery is required for use in producing commodities feeding into non-agricultural production processes (wood, metal lathes etc). We can call this the ‘import-input’ linkage.

(iii) Agricultural raw material production feeds into locally-sited production processes, undertaking further processing before exporting takes place (e. g. timber, meat and wool processing). We call this an ‘output-export’ linkage.

(b) The Level of Exchange: the foreign exchange earned from a( iii) is required to finance linkages a(i) and (ii). The foreign exchange earned from exported manufactures is needed to reproduce production of itself, as seen by linkage a(i).

(c) The level of Finance Capital: seasonal shifts in the demand for credit by the farming sector results in credit being withdrawn at certain periods from this sector and fed into urban manufacturing. The seasonal pattern of production and realisation of export revenues, implies a requirement for foreign exchange credits for purchasing continuously needed materials for manufacturing. The credit system operates to effect these linkages and enables reproduction to proceed efficiently.

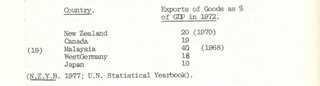

In sum, the basic model is one of the “production of commodities by means of commodities” (Sraffa), but with the crucial extension of all circuits into a foreign counterpart. The high degree of dependence on foreign trade is only partially revealed by aggregate figures relating exports to GNP, where, as can be seen from the table below, N.Z.’s percentage is not particularly high, and corresponds to that of many advanced capitalist social formations.

However, these figures conceal the dependence on particular primary commodities which is a general characteristic of colonies and semi-colonies. Moreover, as the previous discussion demonstrates, a lower aggregate ratio of exports to GDP may merely reflect the extent of indirect linkages in an increasingly diversified economic base. But these local circuits all at some stage spill out into an external one, so such aggregate data as presented in the table can say little if anything about the real degree of dependence or ‘extraversion’ which prevails in the N.Z. semi-colony. For, as is well known, the vital significance of the foreign exchange linkage, in permitting the reproduction of the entire economic base, and obvious from our above illustrations, explains why there has developed such heavy state control of foreign exchange transactions in N.Z.

Although less so than in the past, the evolution of N.Z. capitalism is still strongly dependent on the speed of development of the agricultural branch. Hence minimising the turnover, i.e. the time of production, plus the time of circulation of agricultural capital is critical to the ongoing pattern of accumulation. However, unlike manufacturing, there are natural limits to the capacity of new technology to speed up turnover of capital in agriculture and related branches of production, e.g. forestry. Agricultural produce simply needs a certain time to grow. Limits to the speed of circulation e.g. on account of the physical distance from its markets, are also important and very costly to overcome. This leads to a key point. Any reduction of these limits becomes increasingly costly in its capital requirements, even with heavy state subsidy. The result must be a tendency for the relative profitability of agriculture to lag behind that in other branches and for capital to be redirected accordingly.

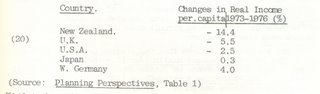

These structural limitations (to which others such as the parcellisation of land could be added) to the development of the productive forces in the branches of primary production will act as real constraints on N.Z.'s overall capacity for accumulation. They also occur in conjunction with a world of heavily protected production of similar commodities in overseas formations whose states place strong limits on the market access for N.Z.'s traditional dairy products, leading to chronic overproduction in those markets that do remain open to N.Z. produce. It follows that the costs of maintaining minimum prices and returns to the smallholder in N.Z. by means of various state subsidies, represent deductions from the total social capital. The fact that these revenues might have been used in more productive branches (in line with the current ideology) reflects the price to be paid for preserving the foreign exchange earnings of the semi-colony. In international ‘comparative’ terms then, N.Z. carries a structural weakness much more significant than in social formations such as W. Germany, Japan etc. , which are not dependent on exports of primary produce, and which are currently said to be forging ahead of N.Z. in the international league tables.

Whilst these figures are clearly subject to severe limitations, taken at face value they can be used to support our structural argument.

The contradictions inherent in the semi-colony' s new, or rather evolved, pattern of circuit interdependence are fairly obvious, but are clarified by means of our analysis of linkages made earlier in this section. For instance, more exports as called for by the orthodox ‘task force’ ideologists (N.Z. at the Turning Point)requires more export production (output-export), in turn requiring more inputs, and more imports (import-output) and so more exports to pay for them etc. Discrete changes in the cost of any one component (e.g. oil costs) are transmitted and probably magnified in their impact (through mark-up pricing practices) on all other components. So, from the above analysis, it follows that increasing export costs lead to reduced export competitiveness (and so on, in a downward spiral).

In addition, the usefulness of across-the-board measures, e.g. devaluation to cheapen exports, have their effects dissipated by the contradictory impact which devaluation has on import costs. This criss-crossing of effects at the level of market forces - prices, terms of trade, incomes etc. - is in truth the realm of the economist number-juggler, whose weighty pronouncements about such complicated interrelationships reflects their function as mystifiers of the underlying relations of production. The consequence of their ideological pronouncements is ultimately to assist in the offensive to drive down the value of labour power in the interests of the “export drive” (Steven, Terms).

3.6 Contemporary Class Structure

In this section we derive the contemporary pattern of social relations (i.e. the class structure) from our analysis of the development of the CMP and the subordinate modes in N.Z. Our approach is simply to locate classes in terms of their qualitative relations as wage labour or capital. We define this relation as one of ‘real ownership’ or ‘real non-ownership’ of capital which determines the form of control of the means of production, the labour process, and the distribution of the surplus-value produced. In our view, ‘legal’ ownership of the means of production is not capital unless accompanied by ‘real’ ownership. Contrary to some views it is meaningless to distinguish between owning either MP, or LP, since the CMP presupposes C (LP+MP) = P. We do not, therefore propose to attempt to quantify the extent to which an individual may be exposed to ‘contradictory’ positions with respect to capital or wage-labour (Wright, Class, Steven, Class). Nor are we concerned at this stage with the reproduction of social relations, or with any imputation of class ‘interests’. We wish to establish first the links between the interlocking circuit model of accumulation, and the formation of a class structure.

From our analysis it follows that two classes produce surplus-value (s) in N. Z. They are:

(1) The working' peasant smallholder (together with-other residual petty capitalist elements of little importance) which we shall discuss below.

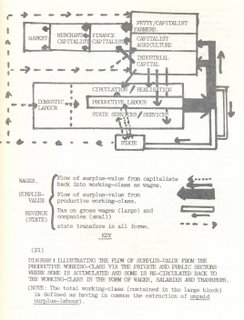

(2) The Productive Working-Class (PWC) , in all branches of production and both private and public sectors. Productive labour is defined by Marx as the production of surplus-value (s) in commodity form, “The worker who performs productive work is productive and the work he (sic) performs is productive if it directly creates surplus-value” (Capital, Vol. I, 1039). This is an important point because it is the exploitation of this PWC that sets the limits to the production and distribution of surplus-value (cf. Wright, Class). All other classes, and fractions of classes, do not by definition produce s , but they are nonetheless engaged in its realisation, its circulation, its accumulation and its consumption. Arising out of the total circuit of capital therefore, it is possible to determine the form in which the social relation, wage-labour and capital, expresses itself in the contemporary N.Z. class structure. (See diagram below).

1. The Working Class

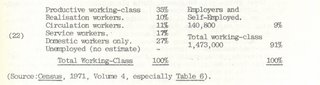

(a) Productive workers: Beginning at the point of production of s in commodity form in all branches of production we have the PWC. Though Marx speaks of ‘direct’ creation of surplus-value it is clear from the context that he includes both mental and manual labour, the “manager, engineer, technologist, the overseer, the manual labourer and the drudge etc” (Capital Vol. I, 1040). The PWC in N.Z. therefore includes not only all those defined as production workers in all industry divisions, but scientists, technicians, graphic artists etc who design and build commodities for the production of other commodities or the consumption of the working-class. See graphic (22) below for an estimate of the total numbers and size of the PWC. Since it is the PWC alone which produces s in the form of commodity capital, C', it is the rate of exploitation of this class of ‘living labour’ which absolutely determines the limits to total s production (excluding the PFM). But while the PWC produces C' it is only one part of the total proletariat (defined as being dispossessed of capital) which functions to circulate capital through its various moments of the circuit, all of whom can be defined as reproductive workers. They include (following the movement of surplus-value through the circuit):

(b) Realisation Workers: all those wage and salary earners engaged in sales (wholesale and retail), advertising, promotion etc, who function to convert C' into M'. This function is performed by employees of capital, public servants on behalf of private capital (e.g. Department of 'Trade and Industry), and public employees on behalf of state enterprises that produce commodities (Gas, Coal etc). They comprise all sales workers (with the exception of those selling financial, business and community etc services) (See Graphic 22. )

(c) Circulation Workers: all those wage and salary earners who are concerned with the circulation of M' as money capital and its conversion into productive capital (exchange for MP and LP) in new productive circuits. They include all forms of commercial workers, banking, finance and administration, both in the private and public sectors. Private sector circulation workers are usually engaged in some aspect of the credit system, advancing M' to finance production or consumption. State circulation workers are those involved in all forms of administration of the public revenue, that is the transfer of s (taxes) from gross wages and salaries, and profits, into all types of productive consumption as capital: first, in the state's own productive enterprises, and second, all kinds of subsidies to the private sector's productive branches. The estimated composition of the circulation working-class consists of the total employed in the major Industry Division, ‘Finance/Business' (less production, sales and service workers) together with clerical and related workers, and professional, technical, managerial etc workers involved in circulation in all of the ‘production’ and ‘realisation’ (sales) industry divisions. ( See Graphic 22)

(d) Service Workers: Those wage and salary earners who exchange services for wages and salaries of the working-class, or who as state employees staff and operate the social services (health, education etc) thereby contributing to the value of labour-power. This group includes all the major division ‘Community-Services’ etc, together with service workers in the production and realisation divisions.( See Graphic 22)

(e) Domestic Workers: This Category of worker is usually ignored by bourgeois economists and placed outside the work1ng-class by Marxists on the grounds that the labour performed is not exchanged for variable capital and is therefore not productive, nor is it exchanged for wages or revenue. It is regarded as a form of “privatised, unpaid, toil” (Adamson, et. al. Women’s).Yet while domestic work is no more productive of s than is realisation, circulation or service work, it nevertheless contributes to the value of labour-power by performing unpaid surplus-labour and reproducing labour-power below its real value. In many cases domestic labour is done by single men and women, and married women, who also perform wage-labour (in N.Z. 50% of women working for wages are married). It follows that there is no strictly separate category of ‘domestic workers’, though it is usually identified as consisting of married women not otherwise working. In our view domestic labour is clearly a case of reproductive labour since it performs the very important function of reproducing the productive and reproductive working-class without which capitalist production would be impossible. The residual category of ‘domestic workers’ should therefore be added to the other categories of reproductive workers in determining the size and composition of the total working-class. ( See Graphic 22.)

(f) The Industrial Reserve Army: Since there are always some individuals(dispossessed of capital) who are unemployed, and the function of the reserve army is to facilitate the production of s through the increased rate of exploitation of all other wage-workers, the unemployed are also reproductive workers (albeit not currently employed). The reserve army, together with the actively employed categories of wage-labour and domestic labour comprise the total working-class.

In the following table we present some estimates of the total working-class relative to capital, and of the relative size of the various sections of productive and reproductive workers comprising the working-class. Because of the limitations of the data, they are no more than rough approximations of the numbers involved in 1971.

Our method of making these estimates was to cross-classify workers according to the major occupational group i.e. type of work - production, service, sales etc. and the major industry division. We classified the industry divisions into production (Agriculture etc; Mining etc; Manufacturing etc; Electricity etc; Construction and Transport etc) and into reproduction (Wholesale etc; Finance etc; and Community etc).

The logic of capital accumulation with increasing concentration and productivity, is to expel ‘living labour’ from production into either the reproductive working-class or unemployment. For example the relative decline in productive workers to reproductive workers is evident in the following:

Similarly, the petty bourgeoisie (those who possess some means of production but do not employ wage-labour) are being progressively squeezed out of existence into the proletariat, even in agriculture where the PFM still accounts for some 65,000 working farmers. For example, in the dairy industry:

It would appear therefore that the familiar polarisation of the two main classes in the CMP is taking place in the N.Z. social formation with the working-class now comprising about 90% of the active working population, and the capitalist class about 10%.

(Note: It should be emphasised that the identification of the working-class at the level of production relations deliberately excludes the fashionable concept of the ‘function of capital’ which is adopted by Wright and others to introduce a conflict of interest between certain categories of wage-labour who whilst performing wage-labour are ‘possessing’ or ‘controlling’ labour on behalf of capital. Whilst it is true that these categories of labour are often higher paid and may not perform surplus-labour this in our view introduces a conflict at the level of distribution of incomes and not production. This, of course, is not to deny the importance of these distributional conflicts along with other ideological and political differences that separate the immediate interests of various categories of wage-labour. The basic point however, is that the difference between these categories is not one given in the relations of production, those who have some function in supervising labour, are not owners of capital in the sense of controlling both means of production and labour process, so whatever differences exist between the immediate interests of the various categories of wage-labour - productive/unproductive, private sector/state, supervisory/non-supervisory etc. – are not conflicts between wage-labour and capital, but conflicts within wage-labour introduced by capital.)

2. The Ruling Class

From what has been said before, the ruling class, which defines the contemporary pattern of control of N.Z. capitalism, will be found to comprise certain definite elements. First, due to the absence of either any established industrial bourgeoisie, or an important landed aristocracy, their place taken be elements reflecting the actual historical process of accumulation in N.Z. Given the ‘facts’ as outlined above, it is not surprising therefore to find the following four major groups represented in the N.Z. ruling class.

a.The old merchant families.

b. The modern finance capitalist (the modem successor to the early comprador).

c. The ‘new professionals’ - lawyers, accountants etc, together with 4.

d. The splattering of ‘ self-made men’ of various descriptions. In terms of numbers of individuals, the group is small (about 100) but they can be defined as the ruling class because they control (actually own) the MP and LP that is brought together in capitalist production in the N.Z. social formation. (N.Z. Herald, Top 100) '!he function of these groups is to integrate, co-ordinate and control, through the various directorships they hold, all the most important industrial and finance companies in N.Z. (NZH, Top 100, Jesson, Family). The technocrats (group 3) are increasingly important in mediating in relations between capital and the state (taxation, inflation accounting, ‘planning’ etc). The ‘pure’ directors on the other hand represent the interests of both foreign and local capital (foreign shareholding amounted to approx. 20% of the total in N.Z. in the '60s but the true degree of foreign control cannot be properly assessed in these terms (see Deane, Economic).

In terms of ‘legal’ ownership of course the ruling class is [still] a minority. This is a consequence of the extensive amount of ‘socialised’ legal ownership of capital in N.Z. both in the form of state shareholding and the ‘pygmy-property’ of thousands of private individuals. But shareholding is as a legal concept, not part of the relations of production. It is the latter which the ruling class controls through their control of management which determines all key decisions affecting the allocation of capital. The separation of the work of management from the ownership of capital as different functions, which is illustrated in the following example, was fully analysed by Marx 100 years before its ‘discovery’ by Galbraith under the now renowned phrase ‘the separation of ownership from control’ (Capital Vol. Ill, 388). (cf. Burnham, The Managerial Revolution)

The way in which the ruling class operates at the level of the economic base and in particular how they dominate the relations of production by determining the distribution of the realised surplus-value, may be illustrated by a concrete example. In the period following the 1975 downturn in market conditions, more and more apparent has been the allocation to management of surplus-value in the form of higher salaries, Mercedes-Benz cars, petrol, housing and other allowances. These deductions are made, not at the expense of the workers, as workers, but at the expense of the pygmy-shareholders (who may of course be workers) whose rates of dividend on their shares consequently fell in 1976 and 1977. Many dividends were declared at low levels, in accordance with a policy of dividend control to discourage the ‘excessive wage claims’ of workers. But in fact, what was occurring as the result of falling profits, was a redistribution of the surplus-value in favour of the managerial group within the ruling class, who received an average or above average rate of profit on their capital, since their dividends were augmented by payments disguised in other forms. The absurdity of taking a legalistic view of production relations is fully illustrated by this example. Legal relations are part of the superstructure. Relations of production determine the allocation of the surplus-value to those legally entitled.

In sum, therefore, the function of the ruling class is two-fold. First, they determine the distribution of surplus-value between the various capitalist and other class fractions within the limits imposed on the reproduction of capitalist social relations due to the contradictions within the CMP (see next section). Second, a point not stressed above, they manage the articulation of N.Z. peripheral capitalism into the international capitalist system. This function brings with it various conflicts which cannot be properly treated here, but which require serious study. Finally, the social composition of the ruling class reflects the historical process of accumulation in N. Z.

3.7 The ‘Welfare State’ and Reproduction

In the preceding sections we have shown how the state played a decisive role in establishing the CMP in the N.Z. social formation by means of its political-legal and economic functions. As a result, capitalist social relations were established in agriculture, and in domestic manufacturing, developing into class struggles between peasants and compradors (see 3.4) and between wage-labour and industrial capitalist classes. In this section we show how the semi-colonial state has functioned to reproduce these social relations at the level of political and ideological relations allowing the full development of the CMP within the N.Z. social formation.

Up until the establishment of the industrial circuit in N.Z. the semi-colonial state functioned largely as a sub-imperial outpost of the imperial state. It drew heavily on the imperial state's political-legal and ideological apparatuses (the imperial army, the Westminster system, statute law etc) which it adapted to the transplanted social institutions in education, trades unions, religion and family relations. However, as we have noted, the local state assumed a much more dominant role in establishing the CMP in N. Z. than had the capitalist states in the historical transition to the CMP in Europe, and it also responded to the growing threat of class struggle arising out of the Long Depression by rapidly transforming its apparatuses, that is introducing ‘state experiments’ to regulate work hours and conditions and provide basic social security measures. The local state therefore assumed a central dominant role in reproducing the CMP in the semi-colonial setting, fusing its accumulation, political-legal and ideological functions in the form of the ‘welfare state’ (Poulantzas, Classes, Intro) .

It is clear that the serious challenge to the reproduction of capitalist social relations posed by the rise of union militancy, forced the ruling class to rely much more heavily on the state's reproductive functions in maintaining social unity and cohesion. But while the state's role was to moderate class struggle and to shift the basis of accumulation from absolute surplus-value to relative surplus-value (i.e. actively reproducing skilled labour-power by means of the state provision of health, education and welfare) it was presented at the level of popular ideology as ‘state socialism’ . The state was conceived to be a ‘neutral’ institution standing above class interests and capable of reconciling these interests in the general interest expressed in terms of the dominant ideology of nationalism. By using the state to reconcile class interests at the level of ideology the ruling class was able to reproduce the conditions for extended accumulation. In so doing, it was in turn able to finance the rising living standards and social services of the working-class and continue state subsidies to capitalist production by means of the rising productivity of labour-power. And rapid accumulation, in its turn, worked to legitimate the state’s appearance as the ‘peoples’ state’. Thus, if the working-class benefitted from higher wages, better conditions, social security etc. it was not because it had won a victory against the capitalist class, but because it had provided these ‘benefits’ out of its own surplus-labour (Bedggood, Class).

The post World War II development of the welfare state has extended its functions in reproducing the CMP and maintaining the unity of the social formation. The use of Keynesian economic policies such as full employment, income maintenance and social security, together with the reproduction of skilled labour-power, sustained the post-war accumulation boom. This had the effect at the level of ideology of legitimating the state’s capitalist role under the slogans of economic growth and per. capita. prosperity. But clearly the state can only manage to appear as the benign ‘people’ state’ so long as its functions do not require any drastic reduction in the living standards of the working-class. So long as it can perform its accumulation functions of reproducing skilled labour-power through the provision of equal opportunity in education, health, housing etc. without raising taxes or cutting wages, these functions will appear to be in the ‘interests’ of the working-class. Indeed, they will serve to reproduce capitalist social relations at the level of individual achievement motivation.

(Note: Most writers (e.g. Yaffe) assume that state intervention in the economy is a drain on the surplus-value going to the capitalist class thereby lowering the average rate of profit. The position taken in this paper is that this conclusion follows from a static analysis which does not take into account (a) the surplus-generating functions of the state which must offset to some extent the so-called ‘drain’ by creating new surplus-value, and (b) the fact that the state extracts surplus-value from the working class (which would not otherwise have gone to the capitalist) in the form of taxation. Thus over the post-war period increased productivity has created more value, but the state has actively intervened in the class struggle for shares of the newly created value by extracting a portion that would have entered into the historical component of the value of labour-power, and cunningly redistributed it to capital. Thus the ideology of the welfare state is the reverse of the reality. (Bedggood, State, cf. Wright, Class, Crisis and the State)

More recently, however, the costs of maintaining the levels of social welfare spending to sustain the illusion of equal opportunity in education, health and so on, has put a strain on the state's fiscal resources, leading to the general situation of cuts in state spending, increased taxation, and the redistribution of state revenue from less productive to more productive branches such as export manufacturing. The basic contradiction between the relations and forces of production which has been suppressed during much of the semi-colony's history by the intervention of the state now threatens to dissolve the unity of the state's reproductive functions. Now that the rate of accumulation has slowed down, the state's efforts in sustaining accumulation require it to redistribute surplus-value from the working-class to the capitalist class. As it takes the offensive against the working-class it sheds its appearance as the ‘welfare’ state and for the first time faces a serious challenge to its ability to suppress class struggle and maintain social cohesion in the N.Z. social formation.

------------------------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment